MINERALISATION

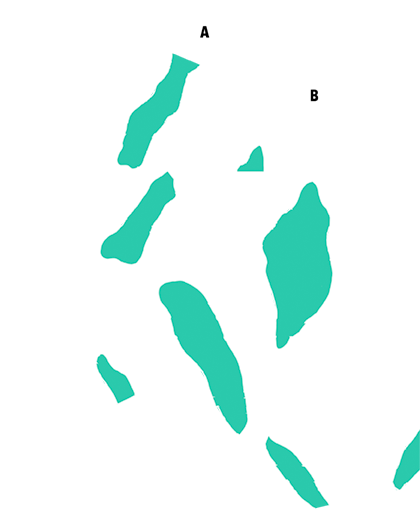

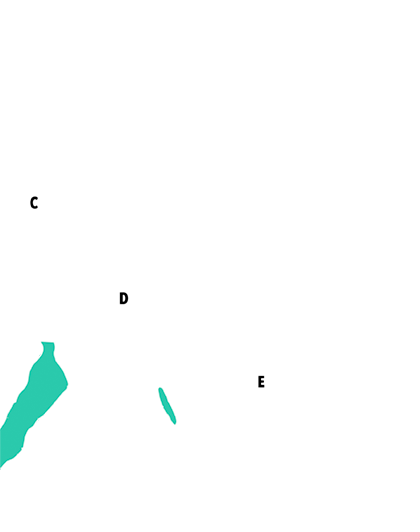

Out of all the ore minerals that exist in this area, one mineral was of particular interest to the mining industry. It was the sulfosalt mineral fahlore. Sulfosalt minerals are complex sulphide minerals where a metal is linked with sulphur. The primary component in the fahlore mined here is copper, representing 35 to 43 % of the mineral. Further components are antimony and arsenic, with the latter generally being more dominant than the former.

The amount of zinc contained in the ore was not unimportant to the local mines. Moreover, the amount of silver that is usually contained in fahlore is relatively low in this area, with values below 1.6 %. The mercury content, on the other hand, is exceptionally high, with recent analyses still showing values as high as up to 20 %. This composition makes the local fahlore a typical schwazite. Interestingly enough, this type of ore is named after the well-known Schwaz silver mines, though it has never been actively mined there.

Chalcopyrite free of silver and mercury is considered the second most important ore mineral. Other ore minerals, including galenite (lead glance), chalcocite (copper glance), and bornite (peacock ore) as well as the extremely common pyrite (fool’s gold), were of no interest to the mining industry. Siderate and limonite were occasionally mined, even if not the primary target of mining. The local ore deposits are assumed to have developed as sedimentary deposits, such as during the Permian age 270 million years ago,

when the rock that had previously formed on top of the phyllite gneiss layer was eroded. The loosened material was mechanically washed away by the local streams and rivers and later collected in a placer deposit. The rock particles collected in this deposit also contained ore minerals, whereby the metals were partly dissolved and removed by the water and precipitated again. During the Alpidic orogeny, extremely high pressure levels and increased temperatures caused the old ore deposit to once again become displaced and accumulated in what would many centuries later become the site of busy excavation activities in the Gand mines.

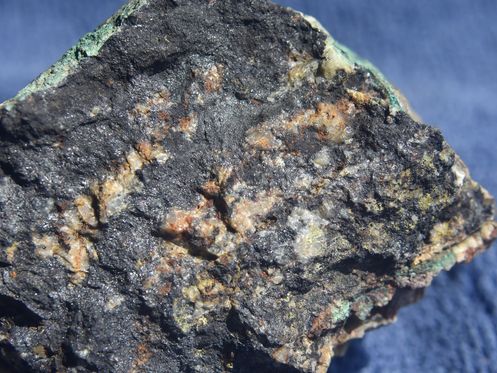

Fig.: A piece of schwazite with quartz streaks that bear iron oxide and secondary (green) copper minerals, primarily consisting of malachite, at the sides; image width: 57 mm; site of the find: Gand

Fig.: Siderite containing quartz (white) and azurite (blue), a typical oxidation mineral of schwazite; image width: 17 mm; site of the find: Gand

A mine was only erected once ore or clear indicators of its presence were found. By following the ore horizontally or in a slightly downward direction into the heart of a mountain, miners often created a highly complex network of adits (horizontal passages), downward-facing ramps, upward-facing raises, and drifts where the ore was excavated. If the ore occurred in parallel layers, the geometry of the mine was usually rather straightforward. The mining process and the creation of underground passages to access the ore was quickly complicated, however, by ore running through different layers of the mountain in streaks.

The deeper miners ventured into the mountain, the bigger the problems they had to face:

- The ore, the overburden, and the water from the rocks that did not drain off, all had to be transported from inside the mines to the entrance over long distances.

- With the distance to the mouth of the mine becoming increasingly longer, the air quality became worse and worse. The use of miner’s lamps and the breathing of the working miners meant that the oxygen was quickly depleted and carbon dioxide contents increased.

A little below the primary adit, a second or even tertiary inclined opening was driven into the mountain in a slightly upward direction. The lowest part of the top adit was thus carefully approached until it was possible to connect the two levels. The benefits of this method were manifold:

- The water that would otherwise have collected inside an adit could drain off by itself.

- Tramps loaded with ore and overburden could be easily hauled out of the mountain, and the empty tramp was easy to push back up the raise.

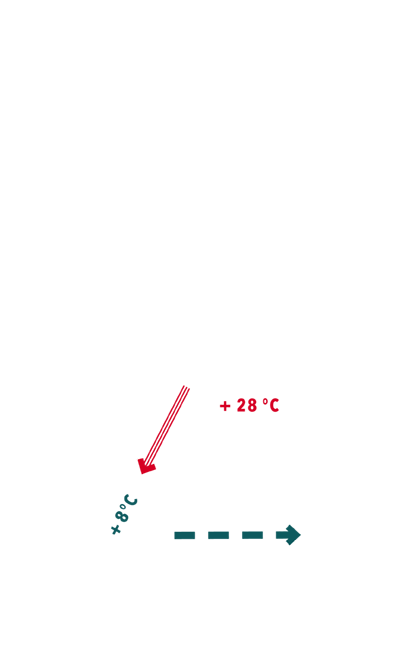

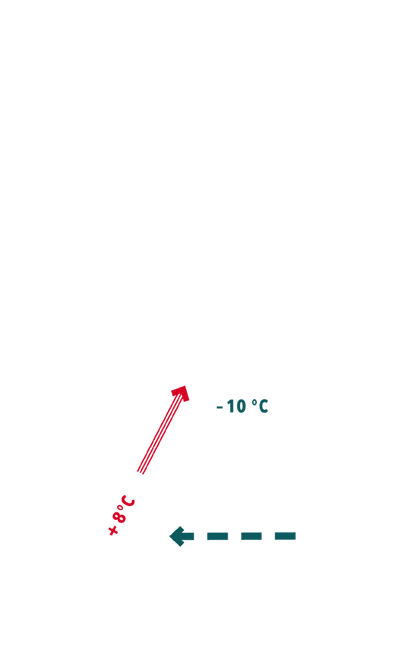

- Based on the fact that only few metres from the surface the mountain holds a constant temperature throughout the year (i.e. 7 °C in Gand), and the outside temperature fluctuates, a natural air circulation or ventilation was achieved. It is interesting to note that, in mining, the term “damp” is used to describe the quality of air inside the mines.

Blackdamp = atmosphere depleted of oxygen

Stinkdamp = usually hydrogen sulphide or sulphur dioxide

Firedamp = combustible gases, principally methane

Whitedamp = poisonous gases, mainly carbon monoxide

Schematic cross-section

of the Gand mines